by Elise Krohn, Native Plants and Foods Co-director

As a resident of the South Salish Sea region, my life is influenced by tides. I notice whether the tide is high or low on my morning walk. A high tide means I cannot walk on my favorite beach. A low tide promises a look into a world that captivates my imagination. This week, as I was standing at the water’s edge just across from the Port of Olympia, I was surprised to see thousands of tiny barnacles rhythmically waving their feathery legs (called cirri) to gather plankton—a water ballet right at my feet! When my eyes settled, I noticed foraging shore crabs, limpets cruising across rocks as they ate algae, and tiny fish darting about. As with so much of the Salish Sea, this beach is teaming with life.

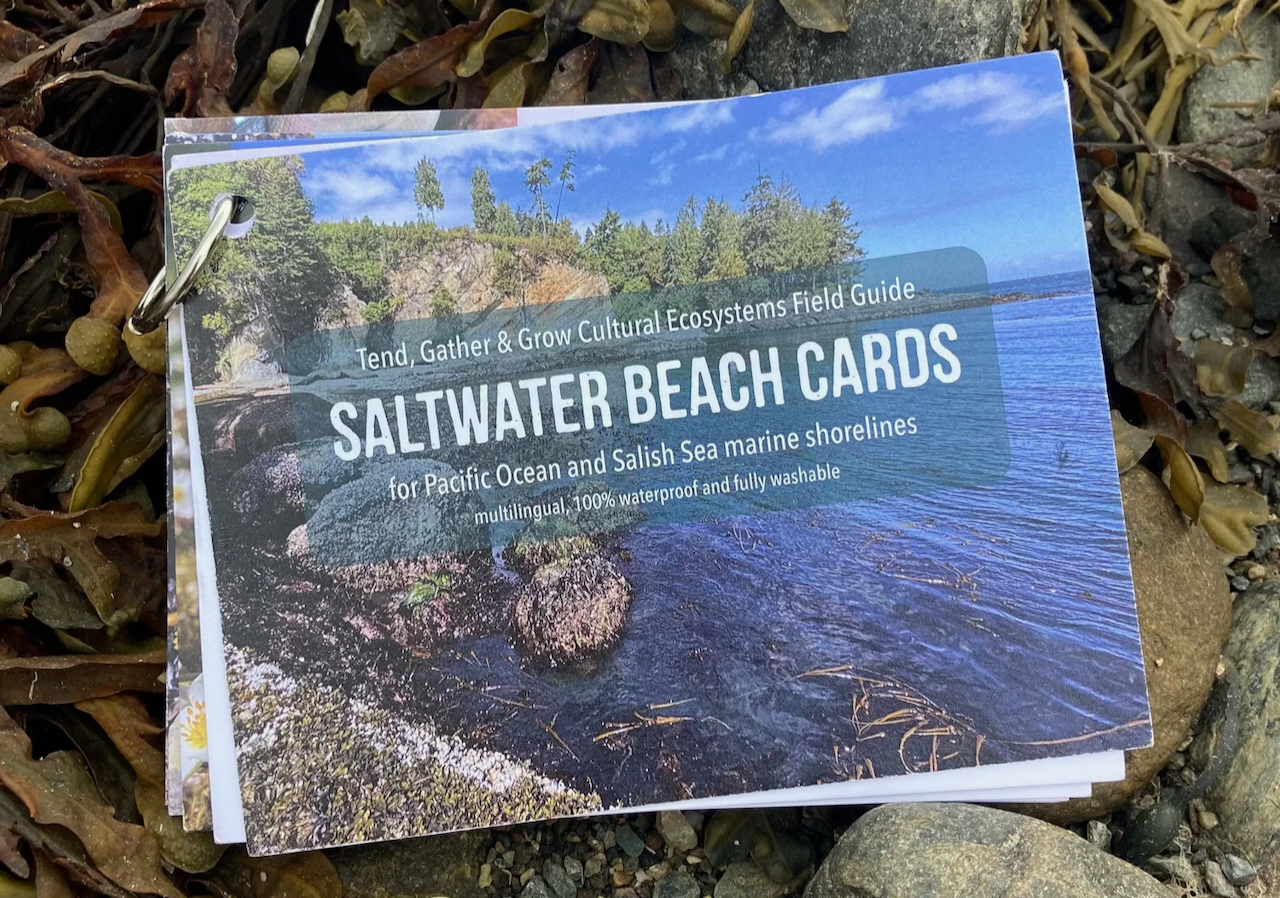

Our Tend, Gather and Grow curriculum development team found great joy in researching and writing the Cultural Ecosystems: Saltwater Beaches overview and lesson. It took years to finish because there is so much to focus on including types of beaches, tidal zones, and the plants and animals that adapt to constantly changing forces between land and sea. It took another two years to finish the Saltwater Beach Cards. These feature 23 common plant and animal species with photos, key characteristics, and fun facts, as well as resources for tending the ecosystem health of shorelines, and sources for further reading. Names for each plant and animal appear in English, Latin, Klallam, Northern Lushootseed, and Southern Lushootseed. The cards are durable and waterproof, and can be ordered from Chatwin Books. We will release a printable version on the Native Plants and Foods Curriculum Portal in early December.

Intertribal Seaweed Harvest

Our team is especially excited about edible beach plants, seaweeds, and seafoods. For the last several years, we have partnered with the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe’s Traditional Foods and Culture Program to host an intertribal seaweed harvest in early summer during the lowest tides. This year, we had over 35 Native harvesters from Oregon, Washington, and Alaska join us to explore the beach, learn about ethical harvesting, and work in teams to cook a seaweed and seafood feast. The Nature Conservancy and the Regenerative Agriculture Fund helped fund the event. Our director of communications, Savannah Romero (Eastern Shoshone) created a short video featuring some of the highlights.

Participants learned about the nuances of seaweed identification and ethical harvesting from Elizabeth Cambell (Spokane/Kalispel), Valerie Segrest (Muckleshoot), Naomi Michalsen (Tlingit), Mackenzie Grinnell (Jamestown S’Klallam), and Jennifer Hahn. Jennifer has supported the event for years and is an experienced forager who has studied seaweed toxicology. We cooked dishes from her newly released book Pacific Harvest: A Northwest Coast Foraging Guide.

We spent half a day cooking in teams and shared a delicious meal including seafood stew with nori, pickled beach asparagus, cucumber seaweed salad, bullwhip kelp pico de gallo and chips, herring roe salad, halibut baked in seaweed, and chocolate ocean pudding with raspberries and a hazelnut crust. Presenters shared Coast Salish stories and insights on how to care for saltwater beaches through restoration and ethical harvesting practices. For example, the Muckleshoot Tribe and Swinomish Tribe have active clam gardens, and Suquamish Tribe is restoring cockle populations. See a video about the Swinomish clam garden here.

.jpeg)

Clam Garden Restoration

Participants learned that the abundance of foods we find on saltwater beaches today is a direct result of Northwest Native American Ancestors, who intentionally cultivated habitat and tended to beaches to nurture the growth of clams and other seafoods. These ancestral beaches are known as “clam gardens” and “sea gardens.” Clam gardens are typically built by rolling rocks down the beach to below the low tide line, creating a low-lying stone wall terrace. These rock walls are seldom visible, except during very low tide. Eventually the area above the wall fills in with gravel, sediment, and broken up shells, creating more area at the same elevation that clams and other bivalves prefer. Acre for acre, a clam garden produces four times the protein as nearby beaches without garden terraces. When the clams spawn, the next generation can drift to nearby beaches, spreading clams to the whole area.

Like many traditional ways of managing lands, clam and sea gardens represent a nudge to the natural system, rather than a replacement. There is no need to add food or fertilizer, and machinery is not required. Clams can be dug with traditional digging sticks that have been used since time immemorial — in fact, the removal of big rocks and the creation of clam beds makes the digging even easier. Harvesting from a clam garden helps to maintain it. Digging aerates the soil, breaks up sediment, and prevents clams from crowding each other out. Clam garden beaches have higher productivity and greater biodiversity. Larger and more diverse populations of species such as sea cucumbers, crabs, and seaweeds are found near clam garden walls.

Like any other garden, clam gardens require regular care to be productive. Seasonally, the sediment is aerated by raking (also called “fluffing”) to avoid sediment compaction and allow more water and air pockets needed for the clams to grow. In addition, seaweeds are cleared from the clam garden area, which helps the clams to breathe better, and are brought upland to feed and nourish the shore plants.

Even if the clam garden walls are not actively managed at present, they will stand for centuries. Nooks and crannies in the rock walls continue to provide shelter and habitat to many species. Archaeologists have studied some of the sea gardens of the Northwest Coast, using barnacle scars and clams that were accidentally buried by the walls to get radiocarbon dates. These show that some clam gardens have been in place for up to 4,000 years!

Clam gardens are an ancient Indigenous technology, and they continue to be helpful for managing modern-day issues such as climate change. Archeologists have uncovered evidence that Indigenous people moved clam garden walls forward and back in the nearshore area or doubled and even tripled the size of the walls, over the past centuries, likely in response to changes in sea level elevation. As sea level rise threatens many areas of the Salish Sea today, clam garden walls can be adapted or moved to protect shellfish areas. The impacts of storm surge waves, which we are experiencing with bigger and more frequent storms, are reduced by the rock walls and the many species of seaweeds that grow on or near the walls. Shell hash that accumulates within the clam garden area may help reduce ocean acidification by dropping the ocean water’s pH levels.

For more information visit the Clam Garden Network. There are many other forms of saltwater cultural ecosystems throughout the Pacific including creating habitat for spawning herring, fish traps and weirs, and estuarine root gardens. To learn more about the various habitats, tending practices, and knowledge associated with sea gardens, see the Sea Gardens Across the Pacific story map and the Indigenous Aquaculture Collaborative Network.

If you are close to the Salish Sea or the Pacific Ocean, we hope you enjoy some beautiful beach walks this winter. Who lives there? Do you see ancient sea gardens at low tide, or are there beaches that are being actively maintained close by? What might you do to uphold the amazing diversity of our precious waters? Check out the Tend, Gather and Grow Cultural Ecosystems Field Guide Saltwater Beach lesson and cards for a deeper dive into the endless wonders of beaches.

*Thanks to Melissa Poe and Jamie Donatuto for their contributions in writing about clam gardens.